- Volumes 84-95 (2024)

-

Volumes 72-83 (2023)

-

Volume 83

Pages 1-258 (December 2023)

-

Volume 82

Pages 1-204 (November 2023)

-

Volume 81

Pages 1-188 (October 2023)

-

Volume 80

Pages 1-202 (September 2023)

-

Volume 79

Pages 1-172 (August 2023)

-

Volume 78

Pages 1-146 (July 2023)

-

Volume 77

Pages 1-152 (June 2023)

-

Volume 76

Pages 1-176 (May 2023)

-

Volume 75

Pages 1-228 (April 2023)

-

Volume 74

Pages 1-200 (March 2023)

-

Volume 73

Pages 1-138 (February 2023)

-

Volume 72

Pages 1-144 (January 2023)

-

Volume 83

-

Volumes 60-71 (2022)

-

Volume 71

Pages 1-108 (December 2022)

-

Volume 70

Pages 1-106 (November 2022)

-

Volume 69

Pages 1-122 (October 2022)

-

Volume 68

Pages 1-124 (September 2022)

-

Volume 67

Pages 1-102 (August 2022)

-

Volume 66

Pages 1-112 (July 2022)

-

Volume 65

Pages 1-138 (June 2022)

-

Volume 64

Pages 1-186 (May 2022)

-

Volume 63

Pages 1-124 (April 2022)

-

Volume 62

Pages 1-104 (March 2022)

-

Volume 61

Pages 1-120 (February 2022)

-

Volume 60

Pages 1-124 (January 2022)

-

Volume 71

- Volumes 54-59 (2021)

- Volumes 48-53 (2020)

- Volumes 42-47 (2019)

- Volumes 36-41 (2018)

- Volumes 30-35 (2017)

- Volumes 24-29 (2016)

- Volumes 18-23 (2015)

- Volumes 12-17 (2014)

- Volume 11 (2013)

- Volume 10 (2012)

- Volume 9 (2011)

- Volume 8 (2010)

- Volume 7 (2009)

- Volume 6 (2008)

- Volume 5 (2007)

- Volume 4 (2006)

- Volume 3 (2005)

- Volume 2 (2004)

- Volume 1 (2003)

► The overall theme is assessing the state of knowledge in powder mixing, including current industrial practice, which relies on empiricism and physical insight.

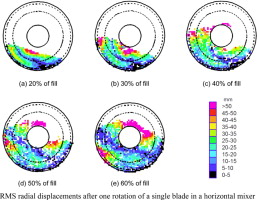

► Lines of research emerging since the mid-1990s are illustrated, these being: computation using DEM, modern instrumentation, and enhanced physical understanding.

► Scale-up rules are hard to develop for some designs, but there are industrial problems, including means of assessing mixture quality, that can now be tackled.

When engineers and scientists encounter the mixing of powders, they enter a subject where it is often difficult to find bearings. This perspective seeks to address this need by setting out the state of practice. It then considers the growing momentum in the area following advances in computation and in measurement that became significant in the 1990s.

The mixing of powders and granular materials is of central importance for the quality and performance of a wide range of products. However, process design and operation are very difficult, being largely based on judgement rather than science. There are not even tabulated data to tell how the quality of mixtures depends on mixer selection. Design depends on experience and insight, not science.

There are no sound scale-up laws for a given equipment type, largely because particle size needs to be included in any dimensional analysis. Design is not possible by applying physical principles. There is no reliable equation to describe the flow of single component powders, let alone multi-component mixtures. In most cases, measurement has been difficult because the materials are optically opaque. Work in the research literature has been questionable because the results obtained for mixture sampling are affected by sample size.

Recently, modern experimental techniques and modelling work have provided a good deal of information on the behaviour of many of the pieces of equipment, though these have been small in size and often confined to materials of a single size. However, the studies have enhanced knowledge of physical behaviour. For example, for a wide range of equipment when operating at lower velocities, mixing is determined by the number of revolutions of the mixer, not the time. Observations of flow structure have led to a few specific models that should scale with equipment size. Measurement techniques are slowly becoming more effective in giving internal flow patterns and in measuring powder composition.

For cohesionless and cohesive materials, DEM (Discrete Element Method) codes are now commonly being used to describe flow patterns on the scale of 10,000–250,000 particles with a few workers using an order of magnitude more particles. A strategy that embraces the effects of particle size, equipment size and internal geometry, is advocated for the future. The aim would be to elucidate engineering principles of general utility. As part of the overall approach, findings must be backed by experiment. For cohesive materials, there is scope to develop methods coming from population balance modelling. There is also scope to develop an understanding by subjecting well-defined cohesive materials to clear patterns of strain.

It may now be possible to use the methods of (say) digital photography to obtain data which can be fed into a method of mixture characterisation that is free of the problems of sample size. Together with an understanding of the relationship between observation at a surface and the average of a flow as a whole, such a method would, if successful, be of immense utility. At the very least, performance charts for industrial equipment would finally become available.

The next stage of development is to build on the emerging knowledge and methods so that the basics for design can be laid down. Then design can become predictable with operation giving effective control of performance.